“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime,” wrote Mark Twain in his wry and widely loved travel book Innocents Abroad, published in 1869.

When Twain first went overseas, he brought America with him. Fashionable Paris charmed the young Twain, but he was ambivalent about learning the language. He often played the brash Yank, unashamed at America’s lack of gilded palaces but awestruck by Russian royalty all the same. He would not be the first artist torn between unquenchable wanderlust and the chance to put down hometown roots—nor the last.

“I came back to Ohio just a few years ago, thinking it was going to be a small stop on my way to the next thing,” says Caitlin Cartwright from her home in Dayton. Until recently the social change artist spent much of her life migrating between international locales after a stateside arts education left her skilled but unemployed and aimless. After graduating with a bachelor in fine arts, she remembers thinking: How am I going to make money from this?

“I ended up doing a 180 and moving to Madagascar for a year,” she says, sounding every bit the awestruck American globetrotter. “I found I really enjoyed it, getting involved in community work. I really liked the idea of immersing yourself in a different culture.”

Cartwright shifted all her creative energy into social work overseas, joining the Peace Corps in Namibia the following year and then relocating to India as part of a graduate program in sustainable international development. When she finally left India for the U.S. after completing her degree, she found herself on familiar turf; it was a blessing in disguise. “Coming back [to Dayton] gave me more physical space,” she says. “Being rooted in one place gave me the opportunity to focus more on painting.”

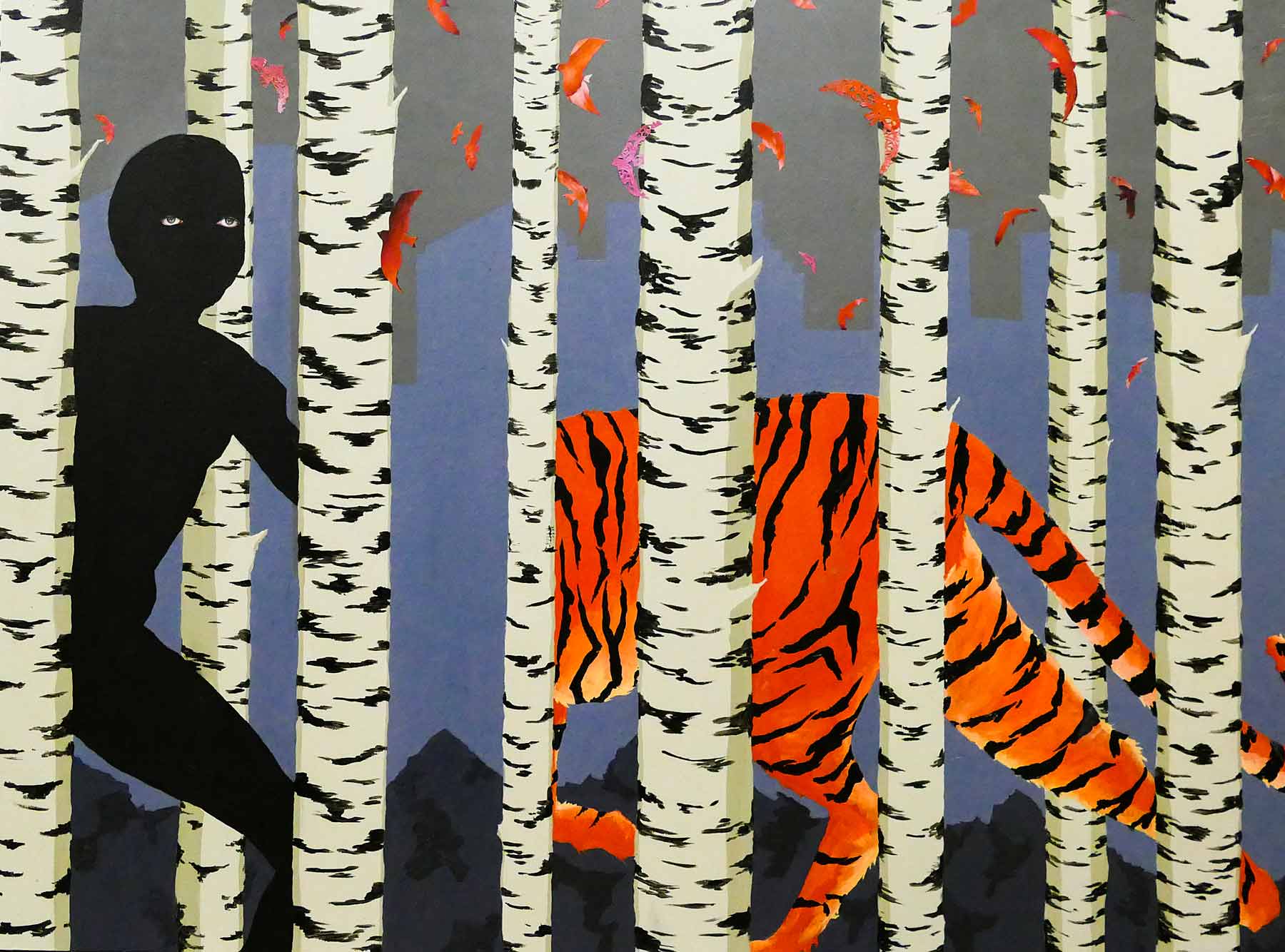

Painting is a loose term for what Cartwright does. She combines swaths of pink, blue, and brown acrylic with patterned papers and pen and ink. They’re more collage than painting. More than that, they’re evidence her time overseas acted as a unifying creative force. The bright patterns, silhouetted figures, and fashion magazine cutouts create a broad narrative dotted with small, intimate moments. Cartwright is an artist who emphasizes hard-won, lived-in moments. Some moments are isolating; others are uplifting. All are healing in one way or another. Only on returning home, she confesses, was she able to translate those personal stories into a sweeping visual narrative.

Cartwright now uses her storytelling skills to strengthen the arts community in Dayton. Her work at the nonprofit We Care Arts fosters healing and hope for Dayton’s disabled community through hands-on arts education. Recently, the Dayton Society of Artists (DSA) asked Cartwright to join their board as Vice President, a role she stepped into with verve. She swears by their weekly newsletter (“chock full of resources”), touts their generosity (“you can borrow photography equipment”), and hosts DSA workshops for artists looking to improve their arts literacy.

As a community leader, Cartwright serves as a judge on several juror panels, sifting through open-call artist submissions for publications, exhibitions, and grants. The expert visual storyteller sees a wide range of portfolios every time she sits down to judge an open call—and she thinks there’s room for improvement. “There are some basic things I think we could all learn to give ourselves a better chance,” she says. She urges artists to think of submitting work as an act of community engagement. “Community is so important to me. And finding ways to connect with each other, wherever your community may be.”

Cartwright shares the keys to connecting with your community, finding your voice, and facing rejection with grace.

Develop a Rich Visual Vocabulary

“Geography has been a driving force behind my work for a long time,” says Cartwright, who collages with locally sourced papers from her travels. The patterns, carefully selected for their cultural meaning, play a crucial role in unifying the work.

“I was really inspired and affected by what I saw around me,” she says of her time overseas. “And I kind of talk about that as my visual vocabulary. Things will stick in my head and they become part of the painting.”

Artists should spend time, she says, exploring the ideas and images that stick in their heads and keep popping up. Cultivating those sticky thoughts and making them stickier will help you develop a cohesive visual vocabulary across your work.

Tell a Damn Good Story

After looking for sticky visual elements, Cartwright says a strong story is next on her list of portfolio desirables.

“I think it’s important to really be cognizant of your point of view, that you’re really showing your voice. I want to see something that shows a unified or unique voice. I always have a pretty specific story or narrative going through my head. My hope is that when someone sees it, they’ll be able to tap [into] it and see a reflection of an emotion they’ve had before.”

A strong story should resonate across all pieces in the portfolio, not just one or two. “I think storytelling is such a powerful thing,” she adds. “I’m not a writer, but I’m a painter, and when I tell my story with painting, it’s universal.”

Decide Which School of Thought to Join

Cartwright is an expert visual storyteller, but she doesn’t relish the task of writing about her work. “It’s such a cliche how much artists hate writing bios or statements,” she says. “I think we’re used to being vulnerable in one way, but writing feels scary in a different way to a lot of artists.”

As a juror, she feels the art world is breaking off into two different schools of thought on arts writing. “One is more traditional and tends to be more art-wonky,” she says. “Kind of academic and insider art-speak.” That’s the model most of us are familiar with. It’s what we learned in school and what we read in gallery pamphlets.

The other model wants to sweep old pretensions under the rug. “It seems like there’s more of a push to be open and explain [the art] so anybody can appreciate and understand it,” Cartwright observes. “Even if they’re new to the art world.”

Her preference? “The academic, flowery [statements], they get abandoned with the quickness. I zone out,” she admits.

Steal From (and Give to) Artists in Your Community

Blurry photos are the number-one mistake Cartwright sees during the judging process. “For a lot of artists, [photos] are in the same basket as an artist statement. They think, ‘Argh, I can’t do it.’ But it’s so necessary.”

Cartwright urges artists to mine their community for resources. “Someone’s going to be a photographer,” she says, noting that artists often travel in the same circles. “What a great way to support another artist by hiring them to shoot your work.”

She also encourages artists to do their research. “I love following painters I admire on Instagram,” she says, often bookmarking opportunities those painters share with their followers for future use. “If I follow them, or we participate in the same show, we probably have similar goals. It stands to reason they’re involved with stuff I might want to look at.” She adds, “If you see something cool, pass it along. Support your community. It’s a two-way street.”

Hunt Down and Face Your Mistakes

The judging process can be subjective, Cartwright says. “It’s important not to take it personally.” To improve your chances, ask questions both before and after submitting. “If someone came to me and asked for feedback, I would give it,” she says. “If you have questions, that’s encouraged. That means you’ll submit a better product. If you write to someone for feedback, it’s not something they owe you. But it’s worth a shot.”

After you get the feedback? “Try again,” she suggests, noting a second portfolio submission landed her a coveted spot in Create! Magazine’s Issue #20: Women’s Edition. Her submission last year was rejected. “That happens all the time,” she says, shrugging off the rebuff. “The curators change, the jurors change. Your work changes. It’s good to have eyes on your work. Even though you might not be right for that opportunity, a lot of times people will remember you. Your name is out there.”

On that last point, she adds a reminder to artists working in a small world: “Be gracious; never send angry emails.”

Head this way to see more work by Caitlin Cartwright or follow her on Instagram.